Brazil faces the second highest rate of deaths from COVID-19 in the world, second only to the United States. As of February 11, 2020, it registered more than 9.6 million positive cases and almost 235 thousand deaths. These numbers represent – approximately – 9% of the infections and 10% of the deaths by COVID-19 in the world.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recently signaled that the pandemic is not yet close to be over yet. Everything will depend on the effectiveness of the vaccines that are currently in process and, even more, on their effective distribution. Now, is that the main health problem facing Brazil?

A group of Brazilian scientists fear for the presence of another much more lethal disease. It is the yellow fever, which would be in danger of breaking out in the Amazon nation once again. According to official figures, 200,000 cases and at least 30,000 deaths are reported annually. That number is more than terrorism and plane crashes combined in one year.

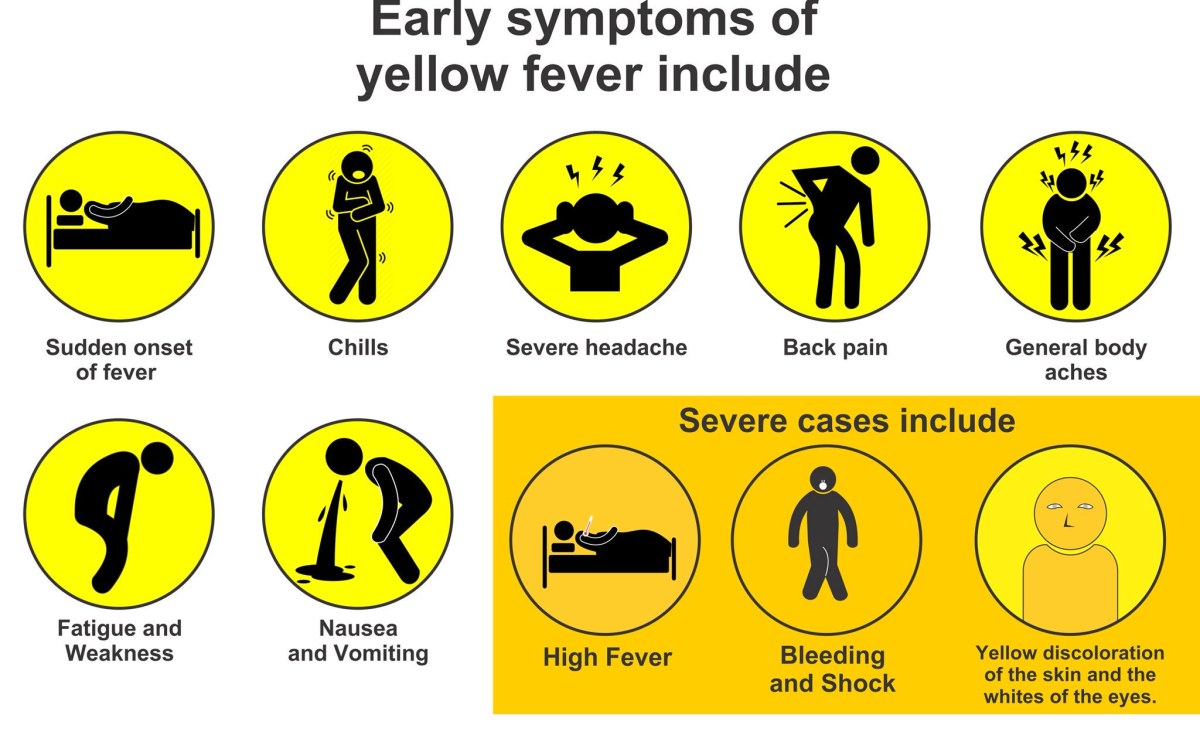

This fever is caused by a virus that is spread between humans and primates through mosquitoes. Its symptoms include a severe fever, headache and, in some patients, jaundice, the yellowish skin color that gives the disease its name. Now, the most serious cases can also cause internal bleeding and liver failure.

The mortality rate – approximately – from this disease is around 15%, if the population is not vaccinated. The percentage is vastly higher than that of COVID-19, which is around 3% globally. The huge difference is that yellow fever has an effective and proven vaccine.

A recent epidemic in Brazil

Recently, Brazil has seen more cases of yellow fever than any other country. In December 2016, an outbreak began in Minas Gerais and spread to neighboring Espírito Santo, both in the middle of the Atlantic Forest. At that time, some 40 million Brazilians at risk of contracting yellow fever lacked vaccines.

Then, in May 2017, the epidemic spread through Brazil, with hotspots in the neighboring states of Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais. However, there were additional outbreaks as far as the northern state of Pará, almost 4,800 kilometers away. It was the worst outbreak in 80 years: more than 3,000 infected and nearly 400 deaths in a matter of months.

In that time, various monkey communities were blamed for the spread of the disease. «When you have primates that are trapped in small forests at a high density … it is easy for all of them to become infected», explained Carlos Ramon Ruiz-Miranda, a conservation biologist at the North State University of Rio de Janeiro.

Quoted by the BBC agency, he explained that in mosquito-infested forests the disease occurs especially quickly between golden lion tamarin monkeys and humans. Because, although mosquitoes are the carriers, it is the human being who makes the situation worse. It does so by invading and destroying forests, as they reduce biological diversity and become closer to other primates.

The vaccine challenge

The forests where scientists are hunting monkeys are located 80 kilometers from Rio, the sixth largest metropolitan area in America. Six hours north, by car, along the Atlantic coast, is São Paulo, the largest city in the hemisphere.

So the proximity of these dense urban areas to forests creates the perfect conditions for an epidemic. But not just any epidemic, one unprecedented since the fever vaccine was discovered almost a century ago.

Now, it is true that yellow fever has a «very effective» vaccine. However, ‘mistrust’ hampers a recent push to vaccinate 23 million people in São Paulo and Rio.

In 2018, the Ministry of Health announced a vaccination campaign for 80 of the 210 million Brazilian inhabitants. In some municipalities, 95% of the residents were vaccinated, but in large cities the rate barely exceeds 50%.

This happened because many Brazilians do not trust the directives of their government when it comes to public health. Currently, with Jair Bolsonaro at the helm, corruption is rampant. So even though the vaccine is free, many assume that this campaign is only intended to benefit those who make these antidotes.

After the 2016-17 outbreak, the same situation occurred today with COVID-19. A lot of fake news was spread on social media and messaging apps, calling the antidote ineffective and unsafe.

In this regard, the WHO asked manufacturers to increase production, but the vaccine «remains restricted due to limited production capacity». As a result, only half of Rio’s residents have been vaccinated against yellow fever.

The population of golden lion tamarin monkeys

The world has around 7.8 billion people, while there are only about 2,500 golden lion tamarin monkeys. So, the scientists put forward a more than interesting proposal. «To stop future outbreaks among humans could we use a novel approach: vaccinate our furry, banana-loving brothers?»

«One way to stop the spread of the disease is to vaccinate humans and the golden lion tamarin», explains one of the researchers, Mirela d’Arc, a biologist from the Federal University of Pernambuco. «If the monkeys are vaccinated, we will have fewer individuals carrying the disease (…) It is herd immunity», she commented.

At first glance, the golden lion tamarin looks like a fiery ball of orange fur. Now, with a mustache and no tail he looks strikingly like the Lorax from Dr. Seuss’s 1971 children’s book. There, a fuzzy creature defends its forest against humans who come to cut down all the trees. Later, it is expelled from her natural environment and forced to leave the forest … Exactly what happens with the golden lion tamarin.

This primate inhabited large swaths of the Atlantic forest in southeastern Brazil in the 1970s. Gradually, logging has cut its habitat into small pieces, to the point that today it is considered a critically endangered species. «Conservationists removed dozens of monkeys from their ever-declining habitat and dumped them into nature reserves outside the city of Rio», says a report in The Guardian.

Currently, the specimens that still live in the wild do not reach 2,500. Most live in fragments of the remaining forest in the São João river basin. Their resistance was enough to reclassify the species from «critically endangered» to «endangered».

The 2017 yellow fever epidemic

Biologist Carlos Ramon Ruiz-Miranda recalls a particular experience during the 2017 epidemic. A farmer took him and his team to the golden lion tamarin in the forest. The monkey tested positive for yellow fever. Later, they found five dead monkeys. By the time it ended, the outbreak had killed more than 4,000 monkeys.

Even among some groups of howler monkeys, the mortality rate was as high as 80-90%. Simply put: primates were already vulnerable. «In the end, we lost 30% of the population, from 2,600 to 3,700 monkeys, in a period of less than a year», said Ruiz-Miranda.

After that, they began to carry out detection tests in neighboring monkey communes. In the end, several of those taken in the sample were positive for yellow fever. In conclusion: the 2017 epidemic showed that not only humans, but also monkeys, are vulnerable to a common disease.

Brazil is home to more species of primates than any other country on the planet. To prevent and not have to mourn a new epidemic, these monkeys may have to be saved first. That is the conclusion reached by the biologist Arc, in the report quoted by the British newspaper.

However, approaching these monkeys for vaccination is not as difficult as it could be with other wild animals. “Generally, animals are afraid of humans. But here, in this fragment, the golden lion tamarins know us”, said D’Arc.

The vaccination of primates

Recently, the Golden Lion Tamarin Association, a non-profit conservation group, got to work on vaccination. The researchers used a small GPS device to record the monkeys’ location, tracking the animal’s movements throughout the forest. Others placed traps loaded with bananas on a handmade wooden platform on the forest floor.

Once they caught enough tamarins, they returned to a lab to examine them. To make sure the monkeys didn’t feel a thing, they sedated them. Then, they did a general health check-up, they measured their weight, body temperature and took fecal, blood and oral samples.

D’Arc dipped a cotton swab into the monkey’s mouth, rubbing it delicately around its tiny teeth. After all that process, they were vaccinated in the lower part of the belly. Afterwards, the team took them back to the forest before they woke up.

By the end of the day, the team had captured, transported, tested, vaccinated, and returned eight tamarins from three different family groups. But their work had just begun. In two years – Ruiz-Miranda says – they plan to vaccinate 500 golden lion tamarins.

In that sense, they urge not to forget an immense detail: like COVID-19, yellow fever may have started with animals. However, it was the human being and our irresponsibility that spread it around the world.

Yellow fever

It is a disease of African origin, which did not exist before the slave trade, according to several studies. It is estimated that it reached the American continent three or four centuries ago. The disease spreads when female mosquitoes bite humans or other infected primates and then bite and infect others.

“Once an epidemic begins, primate species have between four and six days in which they are viremic. This means that the virus is active and the mosquitoes that bite them can become infected”, explained Ruiz-Miranda. So the monkeys thus become «amplifiers» of a mosquito-borne disease.

Currently, the risk is spreading more than ever, especially due to the deforestation of its habitat by man. As the forest in Brazil is decimated, primates are forced to go to smaller areas with higher densities. That puts the animals at higher risk of transmitting infections to each other. Then, with human invasion into those same areas, the risk of those animals transmitting pathogens to humans increases.

«Biodiversity acts as a buffer» against disease, says Ruiz-Miranda. «If you think of an epidemic as an invasive species, the more degraded the environment is, the easier it is for the disease to settle».

The general wake-up call

Researchers say the 2017 outbreak in Brazil was a wake-up call. They even point out that this epidemic illustrated the speed with which humans can spread yellow fever, from one region of the country to another. Today, with the global pandemic of COVID-19, that hypothesis was more than proven.

Finally, the study presented by the scientists ensures that unless more monkeys and more people are vaccinated, yellow fever outbreaks will get worse. By one estimate, Brazil will need 226 million doses of a human vaccine by 2026. Unlike COVID-19, yellow fever is well ahead, as there is an effective and widely available vaccine.