By Bruno Sommer and Denis Rogatyuk

Last Friday, October 23, the Supreme Electoral Court (TSE) of Bolivia officially proclaimed the socialist Luis Arce as president-elect of the country, for the 2020-2025 five-year period, upon approval of the official count of the general elections of October 18.

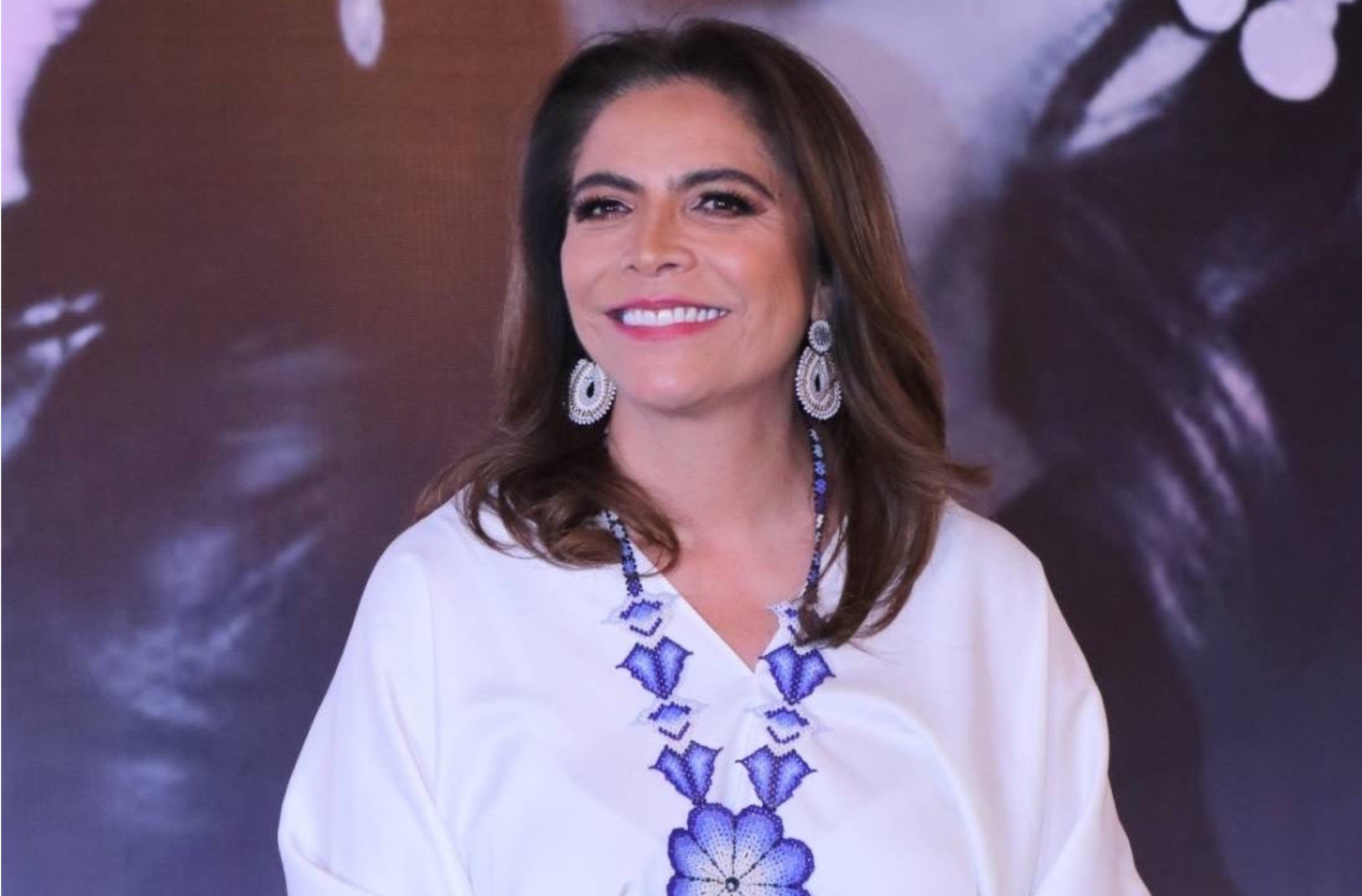

In an interview in Voces Sin Fronteras, led by Bruno Sommer and Denis Rogatyuk, the former president of the Bolivian Senate, Adriana Salvatierra, stressed that this victory ratifies the validity of the progressive project in the region and mentioned the challenges that the new government will face.

DR: You have been traveling all over the country campaigning for MAS, how was the campaign in recent weeks and how do the MAS comrades feel about what they have achieved?

AS: It has been a fairly tense campaign, because the narrative of the electoral fraud was constructed to legitimize what happened in November, which was a coup. Just as we won the elections in 2019, we won the elections in 2020 and now with a margin of difference of 47%, we have reached 55% (of the votes) and that is an important piece of information because the arguments on which they tried to legitimize the coup have collapsed.

The second important element is that it has been a demonstration of the spirit and courage of the Bolivian people. One day before the elections, the government of Jeanine Áñez carried out military exercises and a ‘show’ of the police and military force in the streets seeking to intimidate the Bolivian people. And yet, the Bolivian people made itself present forcefully at the polls with more than 55% support.

It has also been a year of profound learning for us as MAS militants, a year full of pain but one that has opened a path of hope that is widely important for us.

DR: The MAS has obtained 55% of the vote, but also the majority in both houses of the Plurinational Assembly. Was something like this expected and how can we explain those results compared to last year’s elections?

AS: We had established our calculations that we would win in the first round, but I was surprised by the forcefulness of exceeding 50%. I believe that the reason for the victory lies fundamentally in that we interpreted the needs of the population in this adverse context, while there were political parties that disputed who was the legitimate opponent of the MAS or the best opponent of the MAS. We focused on answering the questions that the people had, answering how we were going to regain stability and economic growth, how we were going to promote a new process of job creation, how the economy would be reactivated under the management of Luis Arce and David Choquehuanca , and I think those explanations have been a fundamental difference (with the other political parties).

The second element is that the people have been able to contrast. The opposition that for 14 years questioned and denounced the political project of the MAS, our democratic and cultural revolution, in the exercise of power demonstrated its inefficiency, its inability to manage the State apparatus and, fundamentally, it administered politics around compliance of class interests, to which they respond. And in that contrast, people could see how they were a year ago and how they were now, how their life was organized a year ago, their finances planned and how now all that had collapsed, not only because of the health crisis but because of poor public management.

So, I think that these have been the fundamental reasons, having brought our Government program closer to the real needs of the population, but also having had this period of time where people have been able to contrast political projects and know which ones really obey the needs of the Bolivian people.

BS: After the MAS has been democratically elected by this vast majority, we continue to see various extreme right-wing paramilitary groups that have attacked groups affiliated with the MAS and do not recognize the victory. How has this impacted the social movements, have they been able to resist the different attacks that have occurred and how are they going to address this in the coming weeks?

AS: I believe that in reality what exists is a warming of the street, aimed at strengthening the leadership of Luis Fernando Camacho (for Creemos -We Believe -) in the sub-nationals. Yes, there are paramilitary groups of a fascist nature, but each time they are reduced to a minority, when even Mike Pompeo in the United States recognizes the victory of the MAS, it is recognized by the international community, by the States, international observers, the Supreme Electoral Court itself, the political parties that participated in this election, with the exception of Luis Fernando Camacho. So, I think that it is a position that is becoming more and more a lonely position, more abandoned, lacking an alternative proposal, but that seeks to claim the participation of Luis Fernando Camacho in a local election, in order to make him the valid interlocutor of the region.

DR: Santa Cruz has always been a decisive province in political terms. How do you think the future MAS government will face the problem of separatism and extremism in this region?

AS: I think we are starting from a highly complex scenario to the extent that the MAS no longer has a monopoly on the street, we have a capacity for national mobilization, yes, but we must restructure ourpresence, specifically in the city of Santa Cruz, because the urban area of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, as a municipality, is divided into eight districts. We – of course – have a strong presence in rural areas, however, in the 2014 elections we reached three constituencies, all three in the south-southwest area of our city, and today we have only reached one, and it is quite delicate and complex. that it was lost in Plan 3,000, which has always been considered a bastion of MAS.

So that should call our attention deeply because by losing two constituencies and leaving only one in the urban area, we are in adverse conditions for resistance to a fascist project in territorial terms, this implies the need to restructure the militancy in the territory. But I also think that the most important conflict that surrounds the figure of Luis Fernando Camacho is extreme conservatism and regionalism, a characteristic that has marked his ‘campaign line’ and that has instrumentalized religion as a demographic identity of power, but also that has made use of the regionalism as a flag for imposition on the country, and I think that we do not seek to build that as Bolivians, because we fundamentally believe in integration as an essential element for national development.

BS: What is the future that you see for the Bolivian right? Have they been left without a leader? is there not going to be a real opposition to the MAS in the coming years in Bolivia?

AS: We must not underestimate that. I believe that the position of Fernando Camacho although it is territorialized in the Department of Santa Cruz, cloistered within the departmental limits, we cannot ignore that, and there is a political project behind that. The problem with the political project is that it is one of imposition from the local level to the national level and not of a national nature for integration. And the second conflict that I see around the leadership of Luis Fernando Camacho, is that it is actually the history of the retreat of the forces of the local dominant classes when they are defeated by the emergence of a national political project. We already lived it in 2008 when this scenario of confrontation region versus State was generated and what Álvaro García Linera called the ‘bifurcation process’ took place. The opposition particularly settled in the eastern Santa Cruz tends to return to its territorial nucleus to dispute the local scenarios, mayors, governorships, cooperatives. The institutionalism of the Cruceño falls back to the local ‘spaces’ and from there it proposes to exercise resistance.

What seems complicated to me is the nature of the political project and, beyond that, the scope it has had in the city of Santa Cruz, I think it is something we have to evaluate.

BS: What will be the role of women in this new MAS government? How important should it be? Is there any self-criticism of the previous participation and how should it be in this new period?

AS: We have made profound progress, without a doubt. We are the first country to achieve gender parity in legislative representation instances, even at the local level. We have made great progress regarding the modification of the tenure structure of the land, guaranteeing to go from 15.6 to 46.5 of the agrarian titles in the name of women. We have made progress in regulations that have guaranteed women mechanisms to protect against violence and also political violence. Of course, there is still much to do.

We have to bridge historical distances that were built from patriarchy as a system for the reproduction of gender privileges, I think we should make some reflections on the participation of women and how we (the women) become bearers or not of gender agendas, Being a woman parliamentarian does not necessarily mean that we are bearers of those agendas and we must reflect on this, to the extent that this representation constitutes an important advance for our society.

In addition, I believe that today there is the emergence of colleagues and also young colleagues who remain certain of the validity of the political project. That this is transcending generational borders and that it is guaranteeing its permanence over time as we advance in the materialization of the pillars that we already have, sovereignty, the democratization of wealth and the expansion of opportunities for everyone.

BS: As was Michelle Bachelet in Chile, Cristina Fernández in Argentina, Dilma Rousseff in Brazil, why not in the future an Adriana Salvatierra in Bolivia.

AS: We have just elected Luis Arce and David Choquehuanca. The tasks that we have for now are complex enough to think about that scenario, and I am fundamentally in favor of maintaining the cohesion of our political instrument and of social organizations and I will always support the candidacy that represents the cohesion and unity factor of the revolutionary political entity (the people) in our country that is the fundamental support of this process of change.

DR: What is the future of youth organizations in the Bolivian Revolution?

AS: Chávez once referred to the Venezuelan youth in a congress telling them that they were the best generation not because of what they have conquered but because of the challenge they faced, and I think that today applies to our country. Our generation has fulfilled the enormous challenge to return to democratic paths, to a legitimate government and to recognize the progress and continue walking along a path that guarantees what we have achieved in 14 years, because the emergence of conservative political projects has shown us that it is possible to go backwards in all the conquests that what we considered impossible to go back in. The fact is that it can happen. This has been fully demonstrated by Brazil and the Macri Government in Argentina, but it also has the enormous challenge of making the militancy face itself with a different environment. We have a problem and it is that many young people are probably abandoning the life of workers union participation in the fields, as peasants. They take new forms of organization, they have new ways of communicating, of expressing themselves, and therein also lies the challenge of this generation to continue building that common horizon of ideas using these new tools.

This scenario is highly complex and we hope that our generation, as demonstrated on October 18, will continue to rise to the great challenges.

BS: In which way does the process that the people of Chile are carrying out for the drafting of a new Constitution inspire you and what is your message to the organized citizens of our country?

AS: Admiration. A constituent process is highly complex, because it involves discussing the origin of the construction of the State as a tool for the reproduction of class privileges, gender, and colonial privileges as well, and this interpellation of privileges does not always have a peaceful reaction from the ruling classes, who feel challenged. In addition, they (the ruling classes) often have violent reactions and seek to appeal to ‘flags’ that seem common, and fundamental principles to lead you to a conservative position. For example, in Bolivia they said that the political Constitution of the State approved abortion and they began to make advertisements with images of aborted fetuses, and one said: ‘Wait a minute, nowhere in the Constitution does it say that’, but of course it awakens such a commotion that there were people who believed it, or for example ‘sacred’ private property, they said ‘if you have two houses they will take one away from you’, and the political Constitution of the State not only respects private property but the change process of change in Bolivia gave houses to thousands of Bolivians. Or – for example – they began to play with faith and religion and there were posters that said ‘choose between God and the new political Constitution of the State’, and you said why it is necessary to touch those sensitive fibers that are not part of the essential debate, they weren’t at that time, there were others that were.

But I think that the people and the country do have to prepare to live a strong scenario of confrontation of ideas where they will appeal to the sensibilities of the population and where the possibility of building a different destiny for everyone lies in recognizing historical injustices and building the path from which they begin to be progressively settled. Of course the Constitution is not the answer to everything, there will also come a post-constitutional process that also implies a strong process of mobilization and participation, but if there is something essential in the constituent debate, It is precisely this mobilizing exercise of the population that takes part in the discussion of essential elements of the State for the consolidation of rights.

DR: Do you think Bolivia needs some reforms in the communication field and how you can create new alternative means of communication to compete with the private media and get them out of this place where they can carry out coups d’état?

AS: I think that the media played an important role as a media apparatus in the propagation of the narrative of an electoral fraud that legitimized the coup, but nothing outside of that. The last poll that Página Siete took, said that Carlos Mesa led the vote intention, tied and with a tenth higher than Luis Arce, and you see the electoral result of Sunday and it has absolutely no connection with reality. What does this show you? That – of course – this was a media outlet that was serving the electoral interests of a political force and that delegitimizes it, because clearly, from that. one understands why it attacks the MAS, why so much virulence in the comments, in the headlines, in the creation of an image of living in a dictatorship, of legitimizing and applauding everything related to Carlos Mesa.

After the election, there was even a publication that Carlos Mesa was one of the 30 most influential people in the world to talk about the environment, the one who just lost an election with more than 20 points of difference, that his only gesture with the environment was putting the ashes of the fire in the Chiquitanía in his hands and taking a selfie with that. That was his environmental gesture. But, there you see the role of the media that take a political position. It is legitimate that they can assume a political position, what is neither legitimate nor correct is that they lie about it and the only thing that we demand from the media is truth, truth to inform, for investigation, and to assume a frontal position.

You can not call yourself an independent media if you tie the results of Luis Arce with Carlos Mesa and on Sunday they clearly show you that there was an absolutely different result from the one they informed.

BS: How is MAS preparing for the future? In what way is the MAS going to strengthen the alternative, independent media, and the press beyond that which is part of the public apparatus?

AS: There are two answers to that. The first is that we made an important effort with the creation of community radio stations that also built a balance to the media fence that existed around the construction of a narrative that showed the MAS militants as savages, intolerable people, a political project that seemed destroyed, multiple accusations that they made against us and for which they used the media. We made that effort but we still find that there is also a concentration of the preference of the source from which I communicate, this is not a spontaneous fact, it is fundamentally due to how it is invested in the different media to achieve greater reach. For example, in the emergency behind the truth as an information network typical of Facebook, of social networks, and is the one with the greatest reach, even beyond the official media networks that have a greater reach on television, and we have lived through a highly complex polarization process, I listened to colleagues in El Alto, in the Tropic of Cochabamba, who said ‘on November 11 I turned off the TV and I don’t listen to it until today, because TV misinformation’, they told me.

And I believe that what we should actually build is not alternative media, but rather to strengthen the quality of these alternative media so that they offer products that want to be consumed by the population. I believe that what is essential not only lies in creating and leaving them created but in strengthening the contents so they become attractive to the population, but also contents that contribute to the upholding of certain principles.

DR: What role would you like to play in the new government? What plans do you have, will you continue working with the youth to form new leaderships?

AS: I don’t know what is actually in store for me. I applied for a master’s degree in Human Development and Democratization, I am waiting for the answer. I think that regardless of the public administration post, where I have already worked for five years and I hope to have reached the objectives and the evaluation has been passed positively, militancy does not end only in public service and the contribution to the country is not restricted to a State responsibility, the contribution to the country lies in the academic training that is also necessary to contribute with a greater development of knowledge. I think it is also necessary to return to militancy because otherwise we lose the essence, and I am sure that the colleagues who assume this management (the government), legislative and at the head of the public administration, will be deeply committed colleagues with the social bases from which they emerge.

I don’t know what is in store for me but whatever the responsibility, from the simplest to the most complex, I assume it with full commitment.

DR: What can the international community and the friends of Bolivia do to help the people recover and restore the Plurinational State?

AS: I believe that the reconstruction task is highly complex, of course, but I believe that we must contribute to the strengthening and reactivation of international integration organizations, such as CELAC, such as Unasur, spaces in which the North American tutelage was dispensed with. In those regional entities relations were established between the States and the peoples fundamentally, not based solely and exclusively on a commercial exchange, but also on a solidarity relationship of the peoples and I also believe that those spaces such as Unasur, CELAC, El Alba, which had another logic of exchange between States, must be reactivated and strengthened, because they were spaces that not only contributed to democracy and political stability in the region, but they were spaces over which, in addition, the principle of sovereignty and respect for the options that would have been successful in certain states and it is necessary to rearticulate them.

We feel the absence of those integration spaces precisely in the pandemic, where the States preferred to turn their backs and close the borders instead of contributing jointly to the fight against the health crisis. I believe that this should be an important scenario that we take into account for the reactivation of international relations between States and peoples, based on solidarity and complementarity.

DR: What effect do you think the MAS victory will have on the rest of the continent?

AS: Many were excited about the closure of the progressive cycle, and the victory of the MAS ratifies the validity of this political project, confirms that it is from this side of history that the peoples wish to build a sovereign, dignified future with social justice. And I believe that the victory of the MAS in Bolivia represents that, and also highlights the clear attitude of political intention of organizations such as the Organization of American States (OAS), which all they did was seek to legitimize a coup, become central protagonists, lying to the Bolivian people, and finally ending the lives of more than 34 compatriots and the pain they brought to our families. They (OAS) made us lose a year, they came to disrupt our lives and that must be discussed as well.