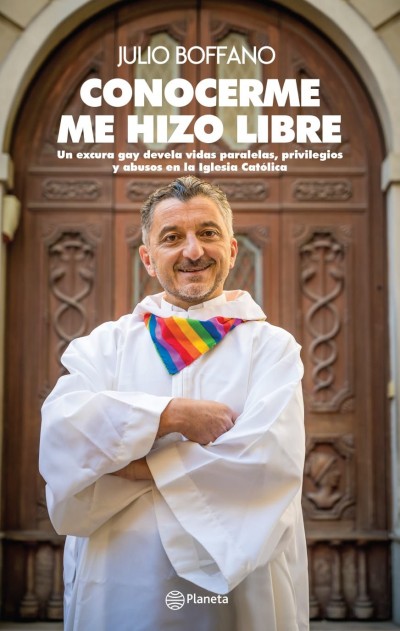

Julio César Boffano was barely out of his teens when he decided to become a seminarian and then a Jesuit priest. His autobiographical book ‘To know myself made me free’ (Planeta Uruguay), which is a best-seller in Uruguay -launched in September and is now in its third edition-.

It can be read as a Bildungsroman, the educational novel of a young man who wants to embrace the Christian priesthood and in the road assumes he is gay. And at the same time, he discovers that the institution of his vocation “has historically been a place of refuge for gays and lesbians”.

According to the author, while the hegemonic religious preaching condemned homosexuality, boys lived in exclusively male communities -and girls with girls- escaping from social and family pressure and without having to explain to their inner circle about why they didn’t get married or didn’t have a girlfriend or boyfriend. But at the same time, Boffano denounces the darkest side of the religious institution: the sexual abuse by priests of children and adolescents that the author recognizes as a systematic practice that the Church insists on «hiding under the rug».

Rome, «the Catholic center of the gay world»

Born in the small town of Paysandú, the author spent a few years in Montevideo until, as a Jesuit religious, he decided to go to Rome, a city he describes as «the Catholic center of the gay world». «Male prostitution is maintained in Italy thanks to the curia», he says in his book. “In the surroundings of the central train station in Rome, priests, bishops and cardinals from the Vatican go to hire sex workers, often young undocumented immigrants from Africa or America who have sex for a few euros. In some cases they go to private apartments. When the priest introduces you to his nephews… They have a lot of nephews; When that happens, be wary».

Installed in the Colegio de la Chiesa de Jesús, the main church of the Jesuit Order in Italy and in the world, Boffano lived with colleagues of various nationalities. “I thought there were no gay Jesuits and it turns out it was full. In the Church, they are referred to as “those who sing in the choir” or “those of the parish”.

What was your objective in publishing the book?

My objective was not to be scandalous. On a personal level it was therapeutic and on a social level, it can work as a help to many people with similar experiences. In the book I narrate my personal process of accepting myself as gay within an institution that condemns homosexuality and also of accepting myself as a survivor of sexual abuse in my childhood. So, the two fundamental objectives were to uncover the hypocrisies in general and in particular the issue of sexual abuse by members of the Catholic Church that, in Uruguay and Argentina, has not yet ‘hit the fan’. In Argentina there are only 60 or 70 priests reported, which is unusual.

What are the difficulties of being a priest and coming out of the closet?

It is very difficult to be an homosexual, and to assume it, within the Church. This statement may seem misleading, but it is true. On the one hand, one is in an enclosed world, full of men and full of gays, and at the same time is part of an institution that condemns homosexuality as an aberrant feeling and practice. More to the practice than to the feeling, but, ultimately, to both. The Maritain Code exists in the Church. It is the “loving friendship”. A man-to-man love that does not include carnal love or sexual attraction; this is sublimated in a chaste love towards the virtues of the loved one. At one point, still in Montevideo, I told myself: I have to tell a trained priest because what I am feeling is a problem. I chose a priest who inspired me confidence, from my vulnerability. “I think I’m homosexual”, I told him and the priest replies: “I’m gay and I’m proud to be”, and he kissed me on the mouth. And he immediately told me: «Do you want to make love with me?». To me, that overwhelmed me. It’s not just wrong, it’s an abuse of authority.

And what happened when you got to Rome?

Arriving in Rome was like arriving in the capital of a boisterous and disorderly party and erotic overflow, at the same time I had encounters and disagreements with my conscience. In Montevideo, before traveling, a fellow Jesuit, who was more clear about my homosexuality than I was, told me: “When you get to Rome, buy a gay guide at any kiosk, and you will learn how to get around the city”. I didn’t know anything about this, I didn’t know that I was going to come across fellow Jesuits and other religious in saunas and orgies.

How did you reconcile during that time what you call gay sexual overflow and being a priest?

What I tell in my book, with some ingenuity, is what it was like to be chosen by God, which is the priestly vocation, and at the same time feel desires and emotions that the institution tells you are sin. So you go the route of asking yourself “Was God wrong?” to “what I am feeling is not so bad”. Unfortunately in Rome, the important thing was that if I had sex, they should not discover me. But the problems with my conscience aimed at not normalizing the hypocrisies.

The sin of Sodom

Except in Leviticus there is no explicit condemnation of homosexuality in the Bible. And there are descriptions of great loves -David and Jonathan, Ruth and Naomi. Did you rely on exegesis?

In biblical times there was no concept of homosexuality and they had very free relationships. The sin of Sodom actually refers to the sin of non-hospitality and has nothing to do with homosexuality as was said centuries later in an erroneous interpretation. “Love your neighbor as yourself”, says the Bible and my interpretation of that motto changed my life. I tried to reflect on these questions and on celibacy in different fields such as in the theology studies at the Pontifical Gregorian University. I also approached Liberation Theology and Queer Theology. What if God were female or gay?

In the book you write that John Paul II and Benedict, particularly, were surrounded by gays. How does that coexist with a homophobic preaching?

The important thing is not to say it, not to let it be known. It doesn’t matter who you sleep with, a superior told me, the important thing is not to let it be known. In the gay case: the most important thing is that you are not a militant of that cause, besides not saying it explicitly. In any case, it is a sin, and a sin is forgiven and one moves on.

Could you help members of the LGTBIQ community from your role as a priest?

Yes, many times. One of the problems was my style of confessor. When they told me «I’m gay, Father», I answered «And what is the sin?». The important thing was to make people reflect if they did wrong to another person or to themselves. After that, the ball began to roll: the priest who confesses on Thursdays is more open. The authorities told me that I had to be more orthodox. I said that I always appealed to the Gospel, I played on the limit. I tried to free gays and lesbians from guilt and transmit that love of God for what is different.

What made you decide to stop being a priest?

I wanted a life without hypocrisy or secret sexual relations. I didn’t want to have to hide being gay, because it’s part of my identity and God made me that way. Also, in my thirties and in Rome, I began to remember that I had been a victim of sexual abuse as a child. There was a moment when I could not be part of an institution that denies, minimizes, victimizes sexual crimes committed against boys and girls. Nor did I want to end up like the cardinal I describe in the book who, being naked in bed with me, makes fun of religious beliefs. I am still a believer and it was not easy to leave.

What was ‘In-ternos’ (In-terns)?

It was an attempt to claim a different way of being a priest. We were a group of gay priests who met to reflect on celibacy and chastity among men. There is fear of talking about celibacy in homosexuality because what is natural in the church is heterosexuality. Celibacy is not only the renunciation of women. What about those of us who are gay? That is not talked about. We reflected on these things to try to be better in our profession. From different positions I criticize both celibacy and chastity as well as confession.

What aspects do you criticize about the confession?

Confession has its pitfalls. They punish more a priest who makes public or wants to denounce a crime that they have been told in the framework of the sacrament of confession, than an abuser. The sacrament forbids you to reveal what has been confessed, which is a trap. Then, the priest sends the victim to pray, to forget.

Why do you maintain that the ICAR (Catholic, Apostolic and Roman Church) became a systematic place to commit sexual abuse against minors?

Because the practice is to deny, hide or pretend that they were ‘exceptions’. The practice is to transfer the abusive priest from one place to another and we know that abuses are not lapses. The abuser continues to leave victims wherever he is transferred. There is a conception that abuse is not a crime but a sin or a disease. The body is what is negative, what needs to be saved is the soul. That is why the priests are transferred from one place to another. The soul must be saved and the body is not subjected to civil and criminal justice. In fact, abusers in the Church feel excused because they convince themselves that they are not breaking celibacy by having sex with males, even boys.

What factors intervene and favor abuse by consecrated religious?

The abuse is committed in a position of power and trust exercised by whoever has that power over the child. A priest or a pastor act as a representative of God with which the behavior of the abuser is doubly perverse. As an ethical mirror, the priest betrays the community he represents. Through the leadership conferred on him, he imposes silence on the community, harming the victims to maintain the institution and its idealized image. That denial and silence are the only ways that not only the hierarchies but also many of the community of believers usually find to rebuild that collective self-esteem, that honesty that they lack. Then, two irreconcilable blocks are formed: those who believe and those who do not believe at all costs, no matter how much they show them the photo. For this reason, I say, let us form the third block, that of the victims and the survivors. The most common thing is that the victim shuts up, and that the family does not believe him or her. To stop denying is to start the process of becoming a survivor.

Why do you believe the Church persists in denying the systematicity of the abuses?

I understand that in any organization there is significant resistance when someone confronts it with these truths in the face. You feel offended. They are issues you don’t know how to deal with. The simplest and most cowardly thing is to deny it, to say that it is a conspiracy. I recommend ‘Don’t Tell Anyone’, a Polish documentary about sexual abuse by the Catholic Church in Poland. There is a moment when the bishops declare that everything is a lie and present it as a conspiracy against ICAR. Suppose it were a conspiracy, shouldn’t it be investigated from an organizational point of view? They ask you to cover up for an erroneous concept of institutional image, and what has worried them the most is not the victims, it is the coffers and the millions that the complaints have cost and will continue to cost, because this continues to happen. As a multinational of faith, it is more important to maintain the increasingly scarce human labor resources, the prestige of the institution and of some people who represent it, than the victims and survivors.

‘Sodom’, sociologist Frédéric Martel’s investigation of the Vatican world, is heavily cited in your book. Do you agree with his hypothesis that the secrecy and repression of all sexuality means that sexual abuse is also silenced?

Martel’s book helped me a lot. He gave it a framework more of research and I narrated a personal experience. In effect, silence functions as a threat. I had contact and sex with cardinals and bishops and I know that some abuser told them «if you ‘fuck’ me with this, I have proof that you are homosexual». It has to do with an institution that silences and denies all kinds of sexuality. In short, if a link can be recognized between abuse and homosexuality within the institution, this is it. All that tangle of silences, protections and influences that exist within the church and that hides all love and sexual ties collaborate and allow the cloak of silence on abuse and also on pedophilia. Because we have a double life, because it is silent, because there are power relations and blackmail. I keep quiet and we all do. Nobody «lifts the partridge» because we do not know where the scandal may end.

You are currently a councilor in a district of Montevideo. Do you define yourself as a gay activist? Do you propose specific policies in this regard?

Yes. My foray into politics is part of my attempt to do things for others, to maintain my vocation to serve that comes from the priesthood. The number of people who contact me after the book has been published is impressive. The fact of being a male child and raped in a patriarchal and sexist society is a separate issue, the effects it produces on subjectivity, relationships and intimacy. The idea is to create a foundation to be able to accompany the process from victims to survivor. Whether it’s because of abuse from priests, sports trainers, uncles or whoever.

With information from Pagina12