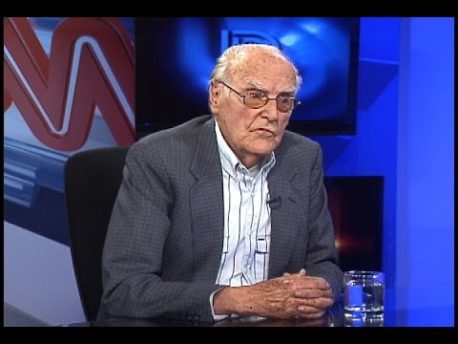

Sigue su curso el arbitraje del “caso Clarin” en el Centro Internacional de Arreglo de Diferencias Relativas a Inversiones (CIADI). Los demandantes, D. Víctor Pey Casado y la Fundación española Presidente Allende, han presentado tres solicitudes ante el Centro con sede en Washington.

Sigue su curso el arbitraje del “caso Clarin” en el Centro Internacional de Arreglo de Diferencias Relativas a Inversiones (CIADI). Los demandantes, D. Víctor Pey Casado y la Fundación española Presidente Allende, han presentado tres solicitudes ante el Centro con sede en Washington.

El 8 de noviembre de 2016 el CIADI tomó razón de la Demanda de rectificación de errores materiales contenidos en el Laudo comunicado el 13 de septiembre de 2016 sobre la compensación debida en ejecución del Laudo de 2008, firme y definitivo, que condenó al Estado de Chile por incumplir sus obligaciones contraídas en el Tratado bilateral entre Chile y España de protección recíproca de inversiones, en particular por denegación de justicia y tratamiento injusto e inequitativo a los demandantes. Dos semanas después, el 22 de noviembre, éstos presentaron una respetuosa propuesta de recusación de dos de los árbitros que deben resolver la Demanda de rectificación de errores, por concurrir un aparente conflicto de intereses con el Estado de Chile. Los demandantes han solicitado suspender el procedimiento de rectificación hasta que se resuelva la Demanda de interpretación oficial del sentido y alcance del Laudo de 2008, presentada en octubre de 2016. Por su interés, EL CLARIN reproduce íntegro el análisis de la presente situación procesal de este arbitraje que el profesor Helpburn, de la Universidad de Melbourne, ha publicado en la revista Investments Arbitration Reporter el pasado 30 de noviembre.

11/30/2016

Three new requests – including double arbitrator challenge – in longest-running ICSID case, Pey

Casado v. Chile

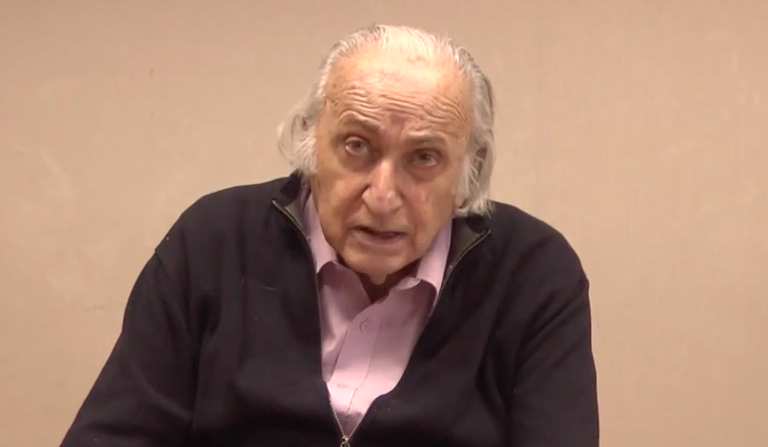

Published: Nov 30, 2016 | By: Jarrod Hepburn

The longest-running case at the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) appears

set to continue for some time yet, as the claimants have filed three new requests with the Washington-based

Centre.

On November 8, 2016, ICSID registered a request by Victor Pey Casado and the Foundation Presidente

Allende for rectification (under ICSID Convention Article 49) of the award issued in September 2016. (That

September award had ruled on the resubmission of some of the claimants’ claims following the partial

annulment of an original 2008 award in the case against the Republic of Chile.)

Two weeks later, on November 22, the claimants filed a challenge against two of the arbitrators that had

issued the September 2016 award (and who would therefore rule on the rectification request, if not

disqualified).

In filing the rectification request, however, the claimants asked the tribunal to suspend that procedure until

the claimants’ further new request – which was filed in October 2016, and which seeks an official

interpretation of the 2008 award under ICSID Convention Article 50 – has been addressed.

The claimants are represented in the case by Garces y Prada Abogados and Gide Loyrette Nouel, while Chile

is represented by Arnold & Porter LLP and Carey & Cia.

Arbitrator challenge focuses on London barristers’ chambers

The double arbitrator challenge stems from the discovery – which the claimants say they made several days

after the September 2016 award was issued – that Alan Boyle, a barrister at Essex Court Chambers in

London, had been engaged to represent Chile in a case against Bolivia at the International Court of Justice.

The claimants observe that two of the arbitrators that issued the September 2016 resubmission award,

Franklin Berman and VV Veeder, are also barristers at Essex Court Chambers. The claimants take issue with

the alleged failure of both the two arbitrators and of Chile to disclose this connection between a fellow

member of their chambers and the respondent state.

In October, the claimants called on Chile, Mr Berman (the tribunal chair) and Mr Veeder (the claimants’ own

nominee) to make full disclosure of all links between Essex Court Chambers and Chile, how much Chile had

paid to other Essex Court members engaged by it, and whether any ‘Chinese walls’ were in place within the

chambers. When the arbitrators and the state declined to provide this disclosure, the claimants filed their

challenge.

According to the disqualification request, both arbitrators declined to respond on the grounds that English

barristers’ chambers were not equivalent to law firms, but were instead composed of separate, independent

practitioners that were under individual duties of confidentiality to their clients. Indeed, the arbitrators are

said to have responded, it would breach legal duties of confidentiality to ask fellow Chambers members to

disclose the identity of all their clients.

In the disqualification request, however, the claimants contend that English law does not prevent the

disclosures, and that, even if there is no relationship of financial dependence between barristers in a particular

chambers (unlike law firm partners), the success of others in the chambers brings general benefits of

‘branding’ to the chambers as a whole.

The claimants add that the IBA Guidelines on Conflicts of Interest in International Arbitration indicate that,

even though barristers’ chambers are not equivalent to law firms, such disclosures by barristers ‘may be

warranted’ in some circumstances.

The claimants express concern over the allegedly ‘coordinated’ responses of Chile and of the two arbitrators,

suggestive – for the claimants – of some link between the tribunal members and the state.

Claimants cite prior case where arbitrator voluntarily resigned due to participation of barrister from

same chambers

Furthermore, the claimants cite the cases (discussed here) of HEP v. Slovenia, in which the tribunal

disqualified counsel for one party from participating in the case on the grounds that he shared chambers with

one arbitrator, and Vannessa Ventures v. Venezuela, in which Mr Veeder himself decided to resign from the

tribunal due to the appearance of another (then) fellow Essex Court Chambers member, Christopher

Greenwood, as counsel for the claimant in that case.

Emphasising arbitrators’ proactive duties to make inquiries and disclose conflicts, the claimants note a further

provision in the IBA Guidelines which suggests that, where professional secrecy rules prevent an arbitrator

from making required disclosures, the arbitrator should resign their post. The claimants recall that Mr

Veeder’s predecessor on the tribunal, Philippe Sands, had applied this principle when he resigned from the

case (see here) due to issues raised by Chile that (Mr Sands said) would have required investigation and

permission from third parties to disclose.

The claimants add that they had themselves proactively disclosed certain connections between their lawyers

Gide Loyrette Nouel and the tribunal secretary appointed by ICSID, and that these disclosures ultimately led

to the secretary’s resignation from the case, at Chile’s request. The claimants question the state’s and the

arbitrators’ reluctance to make similar proactive disclosures.

According to the claimants, Chile had long sought to gain improper control over the tribunal in the case –

even since 1998, when, the claimants allege, the state nominated a Chilean arbitrator despite claiming him to

be of Mexican nationality.

Lastly, the claimants criticise the third tribunal member, Chile’s nominee Alexis Mourre, for agreeing with

the tribunal’s decision not to order Chile to disclose all its connections to Essex Court Chambers. The

claimants suggest that, in his role as President of the ICC International Court of Arbitration and in other

writings, Mr Mourre has approved the idea that all doubts should be resolved in favour of disclosure. His

support for his co-arbitrators, the claimants allege, is at odds with his public commitments to transparency

elsewhere. Despite this, no formal challenge is raised against Mr Mourre.

Claimants seek rectification of 2012 award, but ask to suspend that request until official interpretation

of 2008 award is issued

In the request for rectification of the September 2016 award, the claimants raise four points allegedly

requiring correction.

First, the claimants target a comment in the award relating to the so-called ‘Decision 43’ of April 2000,

which had granted compensation for the 1975 expropriation of the claimants’ publishing business – not to the

claimants, but to third parties who, according to Chilean authorities, then legally owned the business.

Apparently relying on the findings of the original 2008 award, the resubmission tribunal’s 2016 award had

referred to the ‘alleged nullity under Chilean law of Decision No. 43’. However, the claimants say, the 2008

award only discussed the potential nullity of a different decision, so-called ‘Decree 165’ (the 1975

expropriation decree). The claimants suggest that the resubmission tribunal incorrectly referred to Decision

43 rather than Decree 165 at this point.

Second, the resubmission tribunal had elsewhere said that the validity of Decree 165 had never been

questioned ‘before’ the Chilean courts. However, the claimants observe that they did indeed question the

validity of the decree before Chilean courts, and that the tribunal intended to say that the decree’s validity

was never questioned ‘by’ the courts. According to the claimants, this mistake of prepositions required

correction, because it could affect their rights if it was taken as a finding that they had never bothered to

contest the decree’s validity under local law.

Third, the 2016 award suggested that the denial of justice (as found in the original 2008 award) was

consummated ‘by’ the 2008 award. In the claimants’ view, this wording would allow Chile to argue that the

denial of justice was actually the fault of the original tribunal, not of Chile itself. Instead, the claimants say,

the 2016 award should have read that the denial of justice was consummated ‘since’ the 2008 award (ie, that

the 2008 award confirmed the denial of justice earlier committed by Chile).

Fourth, the claimants take issue with the dispositif of the 2016 award, in that it confirmed that, ‘as has already

been indicated by the First Tribunal’, that tribunal’s finding of denial of justice itself constituted part of the

remedy owed to the claimants. The claimants maintain that the original tribunal’s analysis on remedies,

including the view that a finding of denial of justice could itself constitute a remedy, was annulled in 2012.

Because of this, the phrase just quoted (referring to the ‘First Tribunal’) should be deleted, the claimants

argue.

After presenting their claims for rectification, however, the claimants add that the rectification request will

ultimately not be necessary if their request for interpretation of the 2008 award (discussed further below)

serves to clarify matters. The ICSID Convention imposes certain timeframes for filing rectification requests,

the claimants explain, meaning that they were forced to file the request now, even if it might appear

premature given the parallel interpretation request. For that reason, the claimants ask ICSID to suspend the

rectification proceedings until the interpretation proceedings have concluded.

Interpretation request aims to clarify consequences of 2008 award

Meanwhile, in the request for interpretation of the 2008 award, registered at ICSID on October 21, 2016, the

claimants allege that the parties are in disagreement over the meaning of the original tribunal’s finding that

Chile had violated its obligation to accord fair and equitable treatment to the investors and that the latter had

a right to compensation.

The claimants firstly maintain that an ICSID tribunal’s power to issue interpretations of awards under

Convention Article 50 is not limited in time. (The claimants contrast the open-ended wording of Article 50

with Article 51, which imposes an explicit 90-day time limit on requests for revision of an award.)

Amongst other matters, the claimants request an interpretation of the tribunal’s finding that they are entitled

to ‘compensation’. In the claimants’ view, this finding meant an entitlement to some monetary compensation,

while according to Chile, the claimants say, the tribunal did not necessarily intend to confirm any such

monetary right. (This issue was also debated in the 2016 award, as we discussed here.)

The claimants also allege that the parties are in disagreement over whether the original tribunal had

jurisdiction to consider all facts arising after the Spain-Chile BIT’s entry into force, or whether the tribunal

was instead limited to the facts as pleaded in the claimants’ initial 1997 claim.

In addition, the claimants point to debate over the assumptions made by the original tribunal as to the legal

status of Decree 165 in Chilean law. The claimants note that the tribunal had said that, ‘to its knowledge’, the

decree was still valid. However, the claimants call for an interpretation of whether the tribunal had made any

definitive finding on the legal nullity or otherwise of Decree 165, or whether it had merely proceeded in its

reasoning on an assumption that the decree was valid.

According to the claimants, these points of interpretation will have an effect on the consequences that should

flow from Chile’s breach of the BIT, as well as being ‘extremely serious for the integrity of the arbitral

procedure’.

Notably, the claimants also stress that their request for interpretation is purely to assist in determining the

appropriate compensation due for the BIT breach, not ‘a resubmission of the initial claim’.

A request for interpretation of an ICSID award would ordinarily be submitted to the original tribunal

members that issued the award. In their interpretation request, the claimants note that one member of the

original tribunal, Pierre Lalive, is now deceased. The interpretation request does not, however, make any

suggestions as to the appropriate composition of the tribunal to hear the new request. (The other arbitrators

who authored the original merits award were Emmanuel Gaillard and Mohammed Chemloul.)

11/30/2016

Short URL: http://tinyurl.com/j7xguxv